Polypharmacy Medication Review Assistant

Check Your Medication Risks

This tool helps identify potential interactions between your psychiatric medications. It's not medical advice - always consult your doctor.

Select medications and click "Check Interactions" to see potential risks.

When someone is prescribed three, four, or even five psychiatric medications at once, it’s not always because their condition is that complicated. More often, it’s because the system is. Polypharmacy in mental health-taking two or more psychiatric drugs at the same time-has become routine, not exception. In 2005, nearly 14% of Medicaid patients with schizophrenia were on two or more antipsychotics. That’s a fourfold jump from just six years earlier. Today, it’s even higher. And while some of these combinations make sense, many don’t. The real problem isn’t the number of pills-it’s the lack of clarity about why they’re all still there.

Why Do Doctors Prescribe So Many Medications?

It starts with a simple goal: help the patient feel better. When one antidepressant doesn’t fully lift the depression, the next step is often adding another. When anxiety won’t quit, a benzodiazepine gets slipped in. When sleep stays broken, a sedating antipsychotic gets added-not because it’s meant for sleep, but because it knocks people out. This isn’t always based on science. It’s often trial and error, with layers piling up over months or years.

There are real cases where polypharmacy works. Adding bupropion to citalopram can help someone who’s only partially improved. Using a mood stabilizer like lithium with an antipsychotic can control acute mania better than either alone. Short-term use of a benzodiazepine with an antidepressant can ease the initial anxiety that comes with starting treatment. These are evidence-backed moves. But most of the time, what we see is something else: two antipsychotics together, with no clear reason. Or an antipsychotic added to a mood stabilizer just because the patient had a bad episode last year. No new symptoms. No worsening. Just… more pills.

The Hidden Cost: Side Effects and Interactions

Every extra medication brings new risks. Antipsychotics can cause weight gain, high blood sugar, and high cholesterol. Benzodiazepines can lead to memory issues and falls, especially in older adults. When you stack them, the side effects don’t just add up-they multiply. A 2022 CDC study found that people taking five or more medications daily reported significantly worse physical health, lower energy, and more trouble with daily tasks. Their mental distress? That didn’t change much. But their bodies paid the price.

Drug interactions are another silent danger. Many psychiatric drugs affect the same liver enzymes that break down medications. If you’re on sertraline and risperidone, both are processed by CYP2D6. Add a third drug like fluoxetine, and that enzyme gets overwhelmed. Levels of one or both drugs can spike, leading to dizziness, confusion, or even heart rhythm problems. Older adults are especially vulnerable. Their livers and kidneys don’t clear drugs as fast. And if they’re also taking blood pressure meds, diabetes pills, or arthritis drugs, the mix becomes a minefield.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Older adults with schizophrenia are the most exposed group. In recent years, their use of non-antipsychotic medications-like statins, diuretics, or pain relievers-has climbed sharply. These aren’t meant to treat psychosis. But they’re prescribed for heart disease, high blood pressure, or arthritis, which are common in this population. The result? A person might be on four psychiatric drugs and six other medications. That’s ten pills a day. And no one’s stopped to ask: Do we still need all of them?

People in primary care are also at high risk. Studies show that nearly 37% of patients receiving mental health treatment in general doctor’s offices are on complex polypharmacy regimens. These aren’t psychiatrists. These are family doctors trying to manage depression, anxiety, and insomnia while also handling diabetes and back pain. They’re not trained in psychopharmacology. They’re not given time to untangle the web. So they keep what’s there.

When More Isn’t Better

Some combinations have no proof they work. Two antipsychotics together? The evidence is weak. Open-label studies, case reports, and anecdotal experience are not the same as randomized trials. Yet this happens all the time. One drug isn’t working? Add another. It’s not a strategy-it’s a default.

And then there’s the “kitchen sink” approach. A patient walks in with depression, insomnia, irritability, and anxiety. Instead of asking, “What’s the core issue here?” the clinician reaches for a handful of pills: an SSRI, an SNRI, a mood stabilizer, a sleep aid, and an antipsychotic. It’s like throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks. But the wall isn’t the illness-it’s the patient’s body. And it’s getting battered.

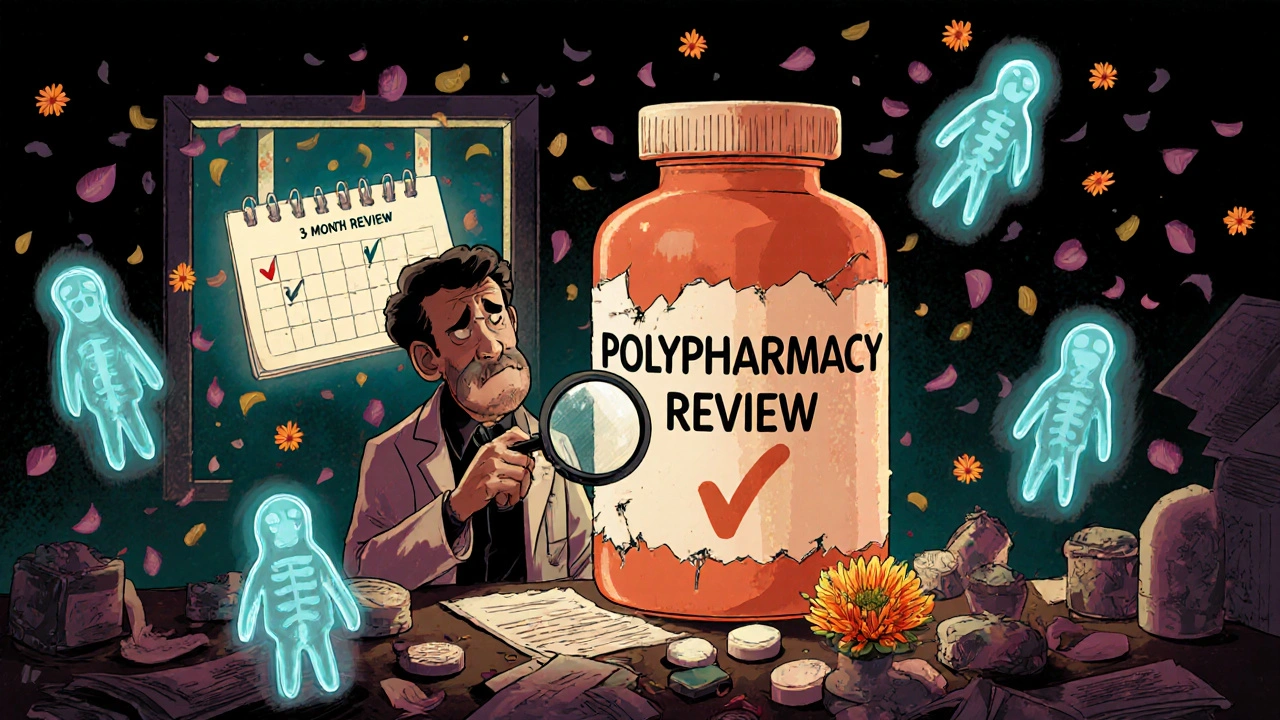

How to Simplify Without Risking Stability

It’s possible to reduce medication burden without causing relapse. A 2024 study tracked patients over 18 months as their regimens were carefully reviewed. On average, they went from 4.7 psychotropic medications down to 2.3. Side effects dropped. Blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar improved. Mood and anxiety scores (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) got better, not worse.

How? Three things made the difference:

- Systematic review-every three months, the whole list was examined. Was each drug still needed? Was it working? Was it causing harm?

- Slow tapering-no cold turkey. Medications were reduced by 10-25% every 2-4 weeks, with close monitoring.

- Patient involvement-people were asked: “Which side effects bother you most?” Often, the answer was drowsiness, weight gain, or brain fog. That became the target.

Some patients were scared. “What if I crash without this?” That fear is real. But with support, education, and slow adjustments, most stayed stable-or even improved.

What’s Changing Now?

Change is coming, but slowly. The American Psychiatric Association now urges doctors to ask: “Could we start with one drug and wait?” before adding more. Treatment algorithms, like those used in Early Psychosis Intervention Programs, have cut antipsychotic polypharmacy by over 80% in some clinics. Pharmacogenomic testing-analyzing a person’s genes to predict how they’ll respond to certain drugs-is becoming more accessible. One study found it reduced adverse reactions by 30-50% in psychiatric patients.

By 2025, over 60% of academic medical centers plan to launch formal deprescribing programs. That means teams dedicated to safely removing unnecessary medications. But right now, 78% of clinics still don’t have a standard process. And many clinicians worry: “What if they get worse?”

That fear is understandable. But the bigger risk is doing nothing. Keeping ten pills going because “it’s always worked” isn’t good medicine. It’s inertia.

What You Can Do

If you or someone you care about is on multiple psychiatric medications:

- Ask for a full med review. Request a pharmacist or psychiatrist to go through every pill, one by one.

- Keep a side effect journal. Note drowsiness, weight gain, tremors, or memory lapses. These are clues.

- Don’t stop anything on your own. But do ask: “Is this still helping? Is there a safer way?”

- Ask about pharmacogenomic testing. It’s not magic, but it can prevent trial-and-error.

- Push for a plan. Not just “more meds,” but “what’s the goal?” and “how will we know if it’s working?”

Medication isn’t the enemy. But unexamined, unreviewed, unchallenged medication? That’s where the danger lies. The goal isn’t to take fewer pills. It’s to take the right ones-no more, no less.

Is polypharmacy always dangerous?

No. Some combinations are evidence-based and necessary-for example, adding bupropion to an SSRI for partial depression response, or using a mood stabilizer with an antipsychotic during acute mania. The danger comes when medications are added without clear goals, without monitoring, or without ever checking if they’re still needed. It’s not the number of drugs-it’s the lack of intention behind them.

Can you safely reduce psychiatric medications?

Yes, but it must be done slowly and with support. A 2024 study showed patients reduced their psychotropic medications from an average of 4.7 to 2.3 over 18 months, with improved mood, fewer side effects, and better physical health. Success depended on gradual tapering, regular check-ins, and patient input. Never stop abruptly. Work with a provider who understands deprescribing.

Why do doctors keep adding medications instead of stopping them?

Time, training, and fear. Most doctors aren’t trained in complex psychopharmacology. They’re under pressure to treat symptoms quickly. Stopping a drug feels riskier than adding one-even if the evidence says otherwise. There’s also fear of relapse, and no standardized protocols in most clinics. That’s changing, but slowly.

Are older adults more at risk from psychiatric polypharmacy?

Yes. Older adults metabolize drugs slower, and their bodies are more sensitive to side effects like dizziness, confusion, and falls. Many are also taking medications for heart disease, diabetes, or arthritis, which can interact with psychiatric drugs. Studies show their polypharmacy rates have risen sharply, often due to non-psychiatric prescriptions. Their risk of hospitalization from drug interactions is significantly higher.

What is pharmacogenomic testing, and can it help?

Pharmacogenomic testing looks at your genes to predict how your body will process certain medications. For example, it can tell if you’re a fast or slow metabolizer of SSRIs or antipsychotics. This helps avoid trials of drugs that won’t work-or could cause dangerous side effects. Studies show it reduces adverse reactions by 30-50% in psychiatric patients. It’s not a magic bullet, but it cuts through guesswork.

What should I ask my doctor about my meds?

Ask: “What is this medication for?” “Is it still helping?” “What side effects should I watch for?” “Could any be stopped safely?” “Is there a simpler way?” And: “Can we schedule a full med review in three months?” These questions shift the conversation from passive acceptance to active partnership.

What’s Next?

The future of mental health treatment isn’t more pills. It’s smarter pills. Better timing. Fewer interactions. And more conversations. As aging populations grow and multimorbidity becomes the norm, the pressure to simplify will only increase. Clinics that adopt structured deprescribing, pharmacogenomics, and patient-centered reviews will lead the way. For now, the best thing you can do is question the status quo-not with fear, but with curiosity. Because sometimes, the most powerful medicine is the one you stop taking.