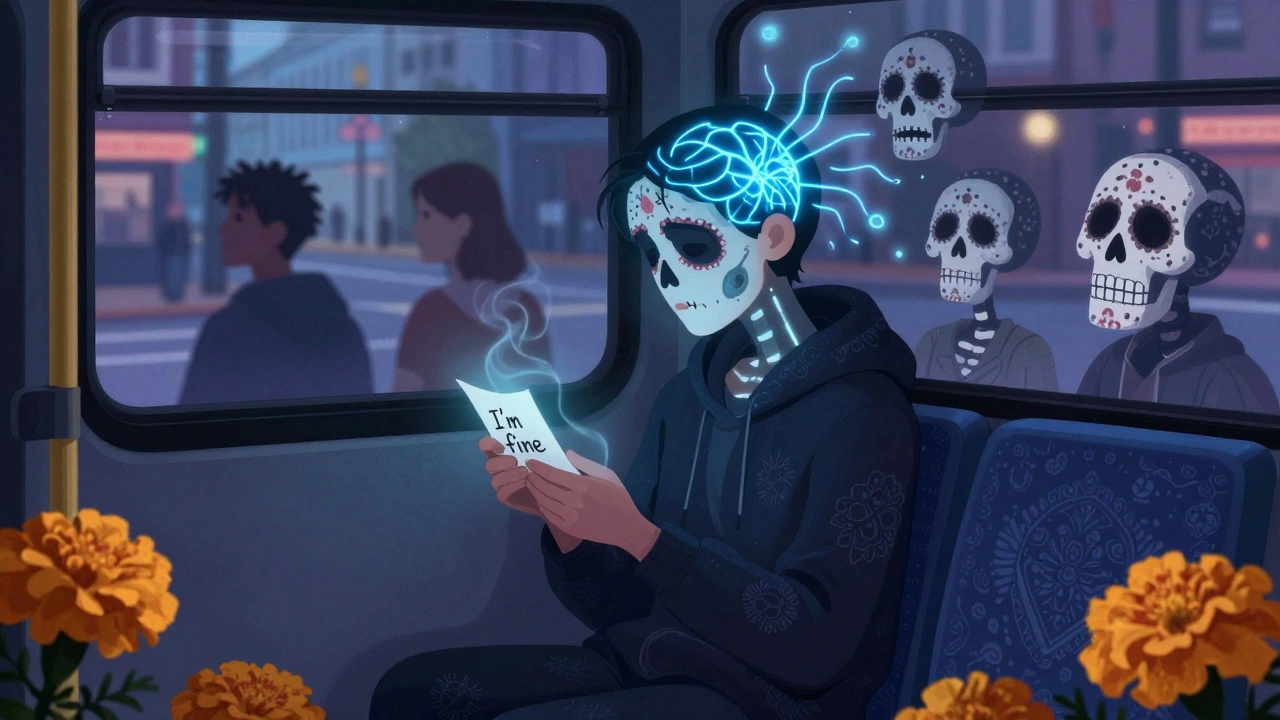

When you have partial onset seizures, your body might jerk, your vision might blur, or you might feel a strange rising sensation in your stomach. But what no one talks about until it’s too late is how these seizures quietly eat away at your mind. The fear before a seizure. The shame after one. The loneliness when friends stop asking if you’re okay. This isn’t just about brain waves-it’s about your emotional life unraveling, one episode at a time.

The Hidden Link Between Seizures and Mood

Partial onset seizures start in one part of the brain, often the temporal lobe. That’s the same area that controls emotions, memory, and how you process fear. When a seizure fires off there, it doesn’t just disrupt your muscles or senses-it stirs up your feelings. People with these seizures are three times more likely to develop depression than the general population. Anxiety isn’t rare either. In fact, nearly half of those diagnosed report constant worry about when the next seizure will strike.

It’s not just the seizures themselves. The brain changes that cause seizures can also make you more sensitive to stress. Your amygdala, the fear center, becomes hyperactive. Your hippocampus, which helps regulate mood, shrinks slightly over time. These aren’t theoretical changes. Brain scans show them clearly in people who’ve had seizures for more than five years. You’re not imagining your sadness. It’s wired into your biology.

Living in the Shadow of the Next Episode

Imagine driving to work, and suddenly you feel that familiar buzz in your chest-the aura. You know what’s coming. You pull over, but you’re still terrified someone will see you. You’ve had this happen three times this month. You stopped telling your coworkers you have seizures because they started looking at you differently. Your boss noticed you were late twice last week. You didn’t say why. You just said you weren’t feeling well.

This is the daily cost of partial onset seizures. It’s not the seizure that hurts the most-it’s the anticipation. The hypervigilance. The way you cancel plans last minute because you ‘don’t feel up to it.’ The way you avoid crowded places, public transit, even showers alone. You start measuring your life in seizure-free days. And when you have one? The guilt hits harder than the convulsion. You feel like a burden. A liability. Like your brain betrayed you.

Depression Isn’t Just ‘Feeling Down’

Depression in people with partial onset seizures looks different than textbook depression. It’s not always crying or sleeping too much. Sometimes it’s numbness. You stop caring about things you used to love. Cooking, reading, hiking-you still do them, but there’s no joy. No spark. Just obligation.

Studies from the Canadian Epilepsy Alliance show that 60% of patients with drug-resistant partial seizures report depressive symptoms severe enough to interfere with daily life. But only 22% are ever screened for it. Why? Because doctors focus on stopping the seizures. They forget to ask: ‘How are you feeling?’

Medications can make it worse. Some antiseizure drugs, like topiramate and phenobarbital, are linked to lower mood. But stopping them isn’t an option. So you’re stuck between two bad choices: seizures or sadness. No wonder so many people feel trapped.

Anxiety: The Constant Companion

Anxiety isn’t just nervousness. For someone with partial onset seizures, it’s a survival mode that never turns off. You check your phone every five minutes for a text from someone who knows your schedule. You avoid elevators, stairs, even swimming pools. You don’t sleep well because you’re afraid you’ll seize in your sleep and no one will find you.

Some people develop a condition called anticipatory anxiety-where the fear of having a seizure becomes worse than the seizure itself. One woman I spoke with in Calgary told me she stopped leaving her house for six months. Not because she was having seizures every day. But because the thought of one outside her home made her feel like she was going to collapse.

And then there’s the stigma. People still think seizures mean you’re ‘crazy’ or ‘unstable.’ You hear whispers at the grocery store. You see the look when you explain you can’t drive. You start lying. ‘I’m just tired.’ ‘I had a migraine.’ You become an expert at hiding.

What Helps-And What Doesn’t

Medication alone won’t fix this. Antiseizure drugs reduce the number of seizures, but they don’t touch the emotional toll. Therapy does. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), specifically adapted for epilepsy, has been shown to cut anxiety and depression symptoms by nearly 50% in clinical trials. It teaches you to challenge thoughts like, ‘I’m broken,’ or ‘No one will ever understand me.’

Support groups matter too. Sitting in a room with others who know exactly what you mean-without having to explain-is powerful. You realize you’re not alone. You’re not weak. You’re just living with a brain that works differently.

Exercise helps. Not because it ‘cures’ anything, but because it gives you back control. Walking every morning. Yoga on weekends. Even dancing alone in your kitchen. Movement tells your brain: ‘You’re still here. You’re still you.’

What doesn’t help? Ignoring it. Telling yourself to ‘just be positive.’ Bottling it up. Waiting for someone else to notice you’re struggling. That’s when things spiral.

When to Ask for Help

You don’t have to wait until you’re in crisis. If you’ve felt hopeless for more than two weeks. If you’ve lost interest in things you used to enjoy. If you’re avoiding people because you’re afraid they’ll judge you. If you’re having thoughts like, ‘I wish I didn’t wake up.’-those aren’t signs of weakness. They’re red flags.

Ask your neurologist for a referral to a psychologist who works with epilepsy patients. Bring a friend to your appointment if you’re nervous. Write down your feelings ahead of time. You don’t need to be ‘broken’ to deserve help. You just need to be human.

You Are More Than Your Seizures

It’s easy to forget, but your identity isn’t defined by your diagnosis. You’re still the person who laughs too loud at bad jokes. The one who remembers everyone’s birthday. The cook who makes the best chili. The dreamer who still wants to travel. The seizures are a part of your life, not the whole story.

Healing doesn’t mean never having another seizure. It means learning to live with them without losing yourself. It means finding people who see you-not your brain’s misfires. It means giving yourself permission to feel sad, angry, scared-and still choose to keep going.

Your brain may have seizures. But your heart? It’s still beating. And that’s where your strength lives.

Can partial onset seizures cause depression?

Yes. Partial onset seizures, especially those originating in the temporal lobe, are strongly linked to depression. The same brain regions that trigger seizures also regulate mood. Studies show up to 60% of people with drug-resistant partial seizures experience clinically significant depression. This isn’t just reaction to diagnosis-it’s biological. Brain changes, medication side effects, and chronic stress all contribute.

Is anxiety common with partial onset seizures?

Extremely common. Up to 45% of people with partial onset seizures report severe anxiety. This includes fear of having a seizure in public, fear of being judged, and anticipatory anxiety-where the dread of the next episode becomes worse than the episode itself. Many avoid driving, social events, or even being alone. This isn’t shyness. It’s a neurological response tied to brain activity.

Do seizure medications make mental health worse?

Some do. Medications like topiramate, phenobarbital, and benzodiazepines are associated with increased risk of low mood, fatigue, and emotional blunting. But stopping them without medical supervision can lead to more seizures, which worsens mental health too. The key is working with your doctor to find a balance. Newer drugs like lacosamide and levetiracetam have fewer emotional side effects and may be better options for people already struggling with anxiety or depression.

Can therapy help with emotional struggles from seizures?

Yes, and it’s one of the most effective tools. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) tailored for epilepsy helps people reframe negative thoughts, manage fear, and rebuild confidence. Research shows CBT can reduce depression and anxiety symptoms by up to 50% in people with partial onset seizures. Support groups, mindfulness, and biofeedback also help. Therapy doesn’t stop seizures-but it stops them from stealing your life.

Should I tell my employer about my seizures?

It’s your choice. Legally, you don’t have to disclose unless your job involves safety risks like operating heavy machinery. But if you need accommodations-like flexible hours, a quiet space to rest after a seizure, or permission to take breaks-disclosing to HR can help. Many workplaces are required by law to make reasonable adjustments. Start by talking to someone you trust, like a manager you feel safe with. You don’t need to explain every detail. Just say: ‘I have a medical condition that sometimes affects my energy. I’d like to discuss how we can make things work.’

What’s the best way to support someone with partial onset seizures and mental health issues?

Don’t offer platitudes like ‘Stay positive’ or ‘Just relax.’ Instead, ask: ‘How can I help?’ Listen without trying to fix it. Offer to go with them to appointments. Help them find a support group. Check in regularly, even if it’s just a text. Avoid treating them like they’re fragile. They still want to live fully-just on their own terms. Your steady presence matters more than you know.