It’s 2026. You’re sitting in a doctor’s office, holding a prescription for an antidepressant. Your teenager just told you they’re feeling hopeless. You’ve read the warning on the bottle: black box warning. Your heart sinks. Does this mean the medicine could make them want to die?

The short answer: it’s not that simple. The black box warning on antidepressants doesn’t say these drugs cause suicide. It says they might increase the risk of suicidal thoughts - especially in the first few weeks of treatment - in people under 25. That’s a big difference. And it’s a warning that’s sparked more debate, confusion, and unintended harm than most people realize.

What Is the Black Box Warning?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the agency responsible for approving medications in the United States. In October 2004, after reviewing data from 24 clinical trials involving over 4,400 children and teens, the FDA made a rare move: it required a black box warning on all antidepressants. This is the strongest warning the FDA can issue short of pulling a drug off the market. It’s printed in bold, black-bordered boxes at the top of every prescription label and patient guide.

The warning says: “Antidepressants may increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults up to age 24.” It applies to every drug in the class - including fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), paroxetine (Paxil), and venlafaxine (Effexor).

The data showed that among kids and teens taking antidepressants, about 4% had suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the first few months of treatment. In the placebo group, it was 2%. No actual suicides occurred in those trials. But the increase in suicidal thinking was real enough for regulators to act.

By 2006, the FDA expanded the warning to include young adults up to age 24. It also required that every patient get a MedGuide - a printed handout explaining the risk. The goal was simple: make sure patients and families knew what to watch for.

Why This Warning Exists

Before the warning, doctors didn’t routinely monitor young patients for worsening depression after starting antidepressants. Some kids felt worse before they felt better. They became more agitated, anxious, or withdrawn. In rare cases, that led to suicidal ideas.

The FDA didn’t invent this risk. It was observed in clinical trials. Independent researchers from Columbia University re-analyzed the original data, blind to which patients got the drug or placebo. Their findings confirmed: the risk was real, even if small.

But here’s the catch: the warning doesn’t say antidepressants are dangerous. It says they carry a temporary risk - usually in the first 1 to 2 months - while the brain adjusts. For many, the medication eventually helps. For some, it doesn’t. And for a very small number, it triggers thoughts they didn’t have before.

The Unintended Consequences

What happened after the warning? The numbers tell a troubling story.

In the two years after the FDA’s 2004 announcement, prescriptions for antidepressants in teens dropped by 22.3%. Visits to psychiatrists for depression fell by 14.5%. Psychotherapy rates also dipped. Meanwhile, emergency room visits for drug poisonings - often intentional overdoses - jumped by 28.6%. And suicide rates among youth rose by nearly 15% between 2003 and 2005.

A 2023 study in Health Affairs looked at 15 years of data. It concluded that the black box warning may have done more harm than good. Why? Because families, scared by the warning, stopped treatment. Doctors became hesitant to prescribe. Many patients never got the help they needed.

One mother in Calgary told me her 17-year-old son refused to take his medication after reading the warning. “It said antidepressants could make me want to kill myself,” he told her. “So I just stopped.” He didn’t go to therapy. He didn’t talk to anyone. Six months later, he tried to end his life. He survived. But he needed hospitalization, intensive therapy, and a year of recovery.

That’s not an outlier. Clinicians across North America report the same pattern: fear of the warning led to avoidance of treatment - and that’s where the real danger lies.

The Real Risk: Untreated Depression

Depression itself is deadly. In Canada, suicide is the leading cause of death for men under 40. For teens, it’s among the top three. Left untreated, depression kills.

The American Psychiatric Association has been clear: the risk of suicide from untreated depression is far greater than the risk from antidepressants. A 2016 statement from the APA said: “For most young people with moderate to severe depression, the benefits of antidepressants outweigh the risks.”

Think of it this way: if you have a broken leg, you don’t refuse a cast because the cast might itch. You get the cast - and you monitor for complications. The same logic applies here.

Antidepressants aren’t magic. They don’t fix everything. But for many, they’re the bridge between feeling trapped and feeling able to get help.

Which Medications Carry the Highest Risk?

The warning treats all antidepressants the same. But science says that’s not accurate.

Studies show the risk varies by drug. Paroxetine (Paxil) has consistently shown higher rates of suicidal ideation in teens. Fluoxetine (Prozac) and Sertraline (Zoloft) have shown lower or no increased risk in multiple studies. In fact, fluoxetine is the only antidepressant the FDA has approved for treating depression in children under 18.

A 2021 meta-analysis in JAMA Psychiatry found that the risk of suicidal behavior was significantly lower with fluoxetine than with other SSRIs. This matters. A one-size-fits-all warning ignores these differences.

That’s why experts now recommend medication-specific guidance. If you’re prescribed an antidepressant, ask: “Is this one linked to higher risk in young people? Are there safer alternatives?”

What Should You Do?

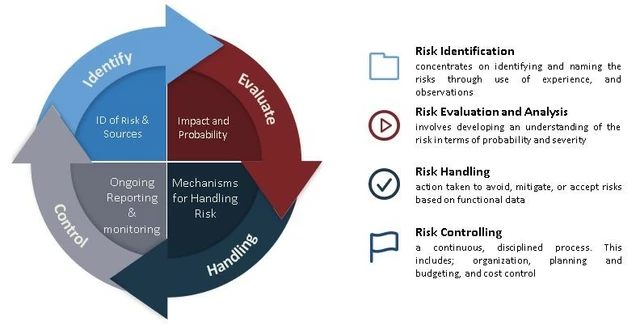

If you or someone you love is starting an antidepressant, here’s what actually helps:

- Start low, go slow. Doses are often lower for teens and young adults. Don’t rush to increase.

- Watch closely for the first 8 weeks. Look for new or worsening anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, irritability, or suicidal thoughts. These aren’t normal side effects - they’re red flags.

- Keep all follow-up appointments. The first visit after starting medication should be within 1 to 2 weeks. Don’t skip it.

- Combine meds with therapy. CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) works better than meds alone. Ask your doctor about referrals.

- Don’t stop cold turkey. Quitting suddenly can make symptoms worse. Always talk to your prescriber first.

And if you’re scared - that’s okay. Talk to your doctor. Ask for the MedGuide. Read it. Then ask: “What are we watching for? What happens if things get worse?”

The Future of the Warning

The FDA held a meeting in September 2022 to review new evidence. They kept the black box warning - but they changed the language. Now it says: “The risk is highest in the first few weeks of treatment. The benefits of antidepressants often outweigh the risks for patients with moderate to severe depression.”

That’s progress. But experts say it’s not enough. The American College of Neuropsychopharmacology now recommends replacing the blanket warning with targeted alerts based on the specific drug, age, and severity of illness.

Imagine this: instead of one warning for all antidepressants, your prescription label says: “Fluoxetine: minimal increased risk of suicidal thoughts in teens. Monitor for 8 weeks.” That’s clearer. More accurate. Less scary.

That’s where we’re headed. But for now, the black box is still there - and it’s still misunderstood.

Bottom Line

Antidepressants don’t cause suicide. But they can, in rare cases, trigger suicidal thoughts - especially early on. That’s why monitoring matters.

On the other hand, untreated depression kills. And when fear of a warning keeps people from getting help, the cost is measured in lives.

The best approach? Don’t ignore the warning. Don’t let it paralyze you. Use it as a guide: start treatment, watch closely, stay in touch with your doctor, and never assume silence means safety. If someone’s feeling worse after starting an antidepressant - don’t panic. Don’t quit. Call your provider. Get help. Right now.