Pediatric Side Effect Detection Calculator

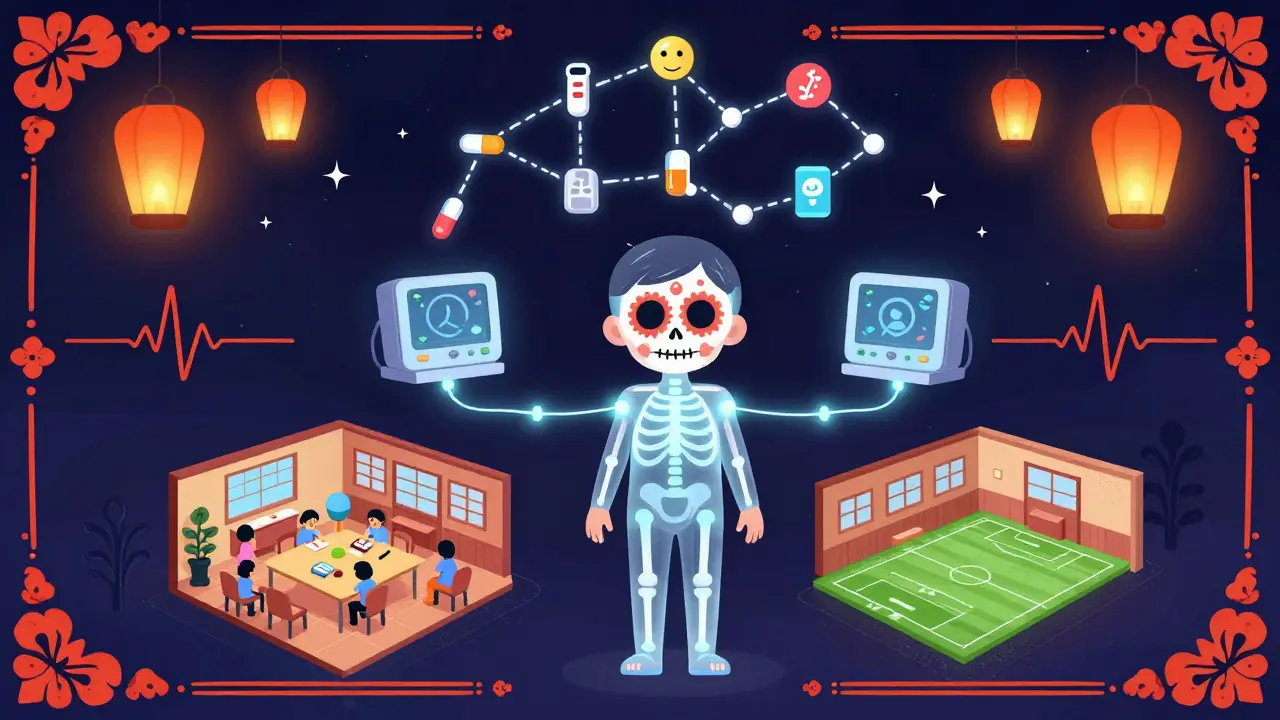

When rare side effects occur in children (like 1 in 200 cases), single hospitals struggle to detect them. This calculator shows how pediatric safety networks use collaboration to find patterns that individual hospitals would miss.

As explained in the article, the CPCCRN network used pooled data from multiple hospitals to detect side effects that would require 500 children to identify in a single site.

With your current sample (only children), you'd detect this side effect . Collaboration is needed to achieve reliable detection.

When a child is given a new medication or undergoes a treatment in the hospital, doctors don’t always know what might happen next. Some side effects are rare. Others only show up after weeks or months. And because kids aren’t just small adults, what works for grown-ups doesn’t always work for them. That’s where pediatric safety networks come in.

These aren’t just research groups. They’re coordinated systems-spanning hospitals, states, and federal agencies-that track what happens to children after they receive care. Their job? To catch side effects early, understand why they happen, and change practices before more kids are harmed.

Why Do We Need Special Networks for Kids?

For decades, most drug trials happened in adults. Then, doctors guessed how much to give children-or skipped testing altogether. The results? Kids got doses that were too high, too low, or just wrong. Some ended up with liver damage, allergic reactions, or behavioral changes no one had predicted.

The 2002 Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act and the 2003 Pediatric Research Equity Act forced a change. But laws alone couldn’t fix the problem. You can’t run big clinical trials for every rare side effect in every hospital. Too few kids. Too few cases. Too slow.

That’s where collaboration became the only solution. Instead of one hospital studying 10 kids over two years, seven hospitals study 500 kids together in six months. Data flows into a central hub. Experts watch for patterns. When a rash appears in three different cities within two weeks, someone notices. And then they act.

How the CPCCRN Built a System to Catch Hidden Risks

The Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN), launched by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in 2014, was one of the first large-scale efforts to do this right.

It wasn’t just about running trials. It was about building infrastructure. Seven major pediatric hospitals joined. A central Data Coordinating Center handled everything: designing forms, calculating how many kids were needed to spot a rare side effect, managing secure data, and running statistical checks. Every site used the same definitions. Every adverse event was recorded the same way.

And there was a dedicated Data and Safety Monitoring Board-experts whose only job was to watch for harm. If a drug caused low blood pressure in 15% of kids in one site but only 2% in another, the board flagged it. They didn’t wait for a lawsuit or a news story. They intervened before more kids were exposed.

One clinical site leader later said the centralized sample size calculations saved their study. Without it, they would’ve enrolled too few children to detect a side effect that only happened in 1 out of 200 kids. That’s the power of scale.

The Child Safety CoIIN: Preventing Harm Before It Happens

Not all pediatric safety work happens in hospitals. The Child Safety Collaborative Innovation and Improvement Network (CoIIN), run by the Children’s Safety Network with support from HRSA, focused on the outside world.

Think car seats, bike helmets, poison prevention, and even teen dating violence. These are the things that kill more children than cancer or heart disease. But measuring their impact? Hard. How do you prove a new school program reduced sexual violence? You track data-real-time, on the ground.

CoIIN gave 16 states tools: worksheets, training, and ways to collect data as programs ran. One team noticed their sexual violence prevention program wasn’t working as expected. Instead of pushing harder, they looked at the numbers. They found teens weren’t engaging with the material. So they redesigned sessions to include real stories, peer leaders, and dating safety tips. The change cut incidents by 22% in six months.

This is the opposite of drug trials. No pills. No IVs. Just communities, data, and the courage to change course when the numbers say so.

What’s the Difference Between Hospital and Community Networks?

CPCCRN and CoIIN both tracked side effects-but they saw different kinds.

CPCCRN focused on medical treatments: drugs, surgeries, ventilators. They caught allergic reactions, organ toxicity, or unexpected neurological changes in ICU kids. Their strength? Precision. They could link a side effect to a specific drug dose, timing, or interaction.

CoIIN looked at environmental and behavioral risks. A new helmet law? Did more kids wear them? Did fewer get head injuries? A school-based mental health program-did it reduce self-harm attempts? Their strength? Scale and real-world context. They saw how policies played out across cities, schools, and homes.

CPCCRN had a built-in safety board. CoIIN relied on state teams self-reporting outcomes. That’s a trade-off. One is tighter, more controlled. The other is messier, but reflects how kids actually live.

What Made These Networks Work?

It wasn’t just funding. It was structure.

- Standardized data: Every site used the same terms. No more “mild rash” vs. “skin irritation.”

- Central analysis: Stats experts found patterns no single hospital could see.

- Fast feedback: If a side effect showed up, the network adjusted within weeks-not years.

- Governance: Steering committees, protocol review boards, and safety boards kept things fair and focused.

And they didn’t try to do everything. CoIIN teams learned quickly: trying to fix 10 problems at once was impossible. They narrowed down to 2 or 3. That’s when real change happened.

What Happened After the Grants Ran Out?

The CPCCRN’s original funding ended in 2014. CoIIN wrapped up its second cohort in 2019. Does that mean the work stopped?

No. The infrastructure lived on.

NICHD used CPCCRN’s model to launch the Pediatric Trials Network under new funding mechanisms. States that participated in CoIIN kept using the data tools they built. Some now track opioid overdoses in teens. Others monitor concussion recovery in youth sports.

The lesson? These networks aren’t projects. They’re blueprints. Once you prove you can catch side effects faster, safer, and smarter, you don’t go back.

Why This Matters for Parents and Doctors

As a parent, you want to know: Is this treatment safe for my child? The answer isn’t in a drug label. It’s in what happened to 5,000 other kids across the country.

As a doctor, you don’t have to guess. You can say: “In the last year, 12 kids on this drug had liver enzyme spikes. We now check levels at week 2 instead of week 4.” That’s evidence. That’s safety.

These networks turned scattered reports into reliable knowledge. They turned fear into action. And they proved that when hospitals, states, and researchers work together, kids don’t have to be the last to benefit from safe care.

What’s Next?

The next wave is integration. Right now, hospital safety data sits in one system. School injury data in another. Emergency room records in a third. The goal? A single, secure network that follows a child from the ICU to the classroom to the sports field.

Imagine knowing that a child who had a concussion in soccer also had a reaction to an antibiotic two months earlier-and seeing if the two are connected. That’s the future. And it’s built on the work these networks started.

It’s not perfect. Funding still comes in bursts. Not every hospital joins. Not every state has the resources. But the model works. And for children, that’s everything.